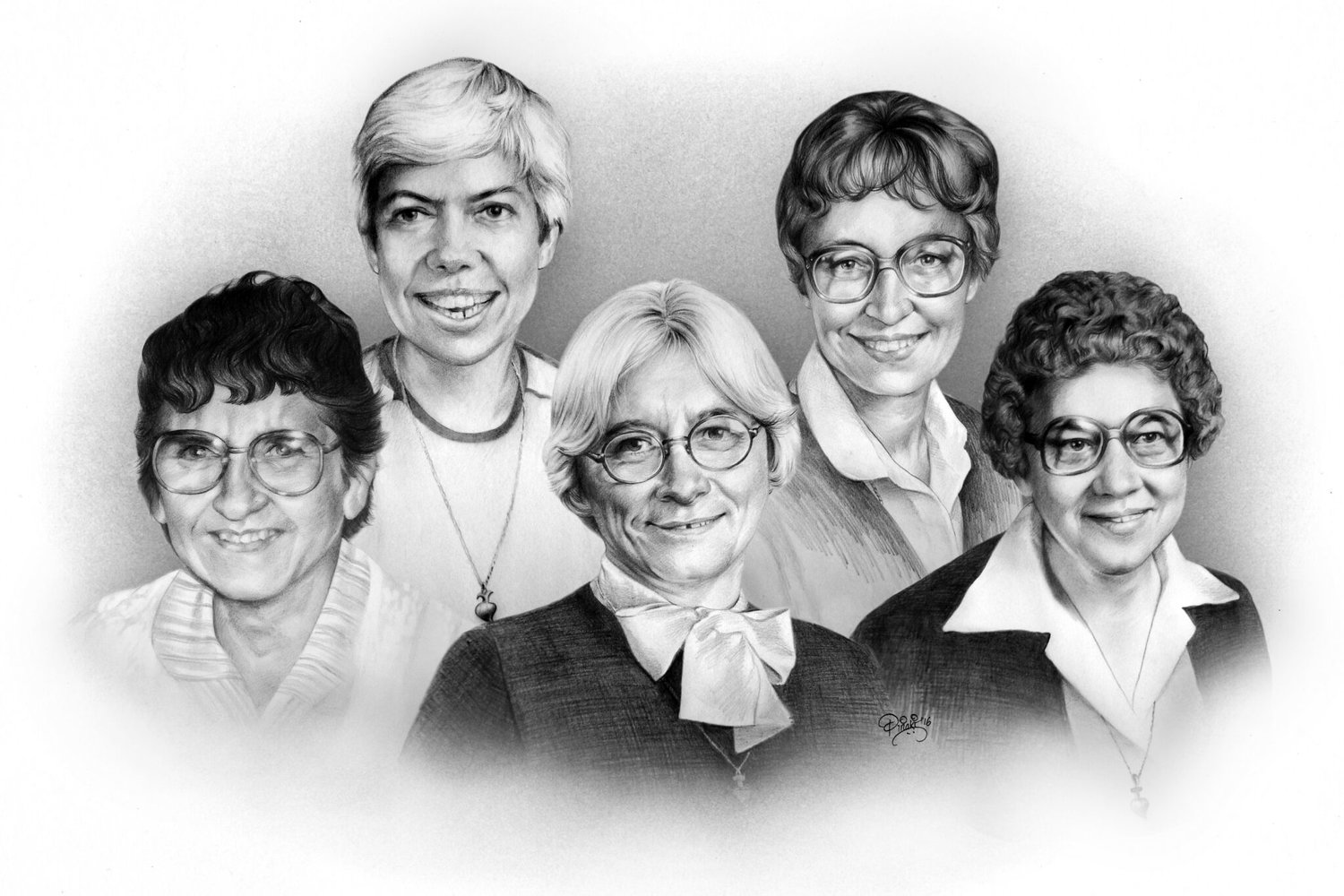

Sr. Kathleen McGuire ASC, known as one of the five Martyrs of Charity, remembered 30 years after their deaths

“We were privileged to have experienced their love and concern for their fellow persons. We shall never forget their memories.”

The words of Archbishop Michael K. Francis of Monrovia, Liberia, still resonate with people in the Jefferson City diocese.

Archbishop Francis was responding to the murders of five sisters who were Adorers of the Blood of Christ, 30 years ago this month.

Two of the sisters had served in this diocese before discerning a call to mission in the war-ravaged West African nation of Liberia.

Sister Agnes Mueller ASC had served in the diocese’s Religious Education Office for two years in the early 1970s.

Sister Kathleen McGuire ASC had served for four years as director of Catholic campus ministry at Lincoln University in Jefferson City.

Joining them in giving their lives were Sister Shirley Kolmer, Sister Mary Joél Kolmer and Sister Barbara Ann Muttra.

Holy and humble

Sr. Kathleen in particular left indelible memories with people in this diocese.

“She had the life and love of God shining through her in every move she made,” said Carolyn Saucier, who was a member of the Lincoln University Newman Center’s board of directors during Sr. Kathleen’s time in Jefferson City.

“She was really a holy, humble woman,” Mrs. Saucier stated. “We all felt so cherished by her. And she was cherished by us.”

Mrs. Saucier remembers a time when her husband was out of town and one of their young children knocked over the mantle and broke all the family’s First Communion mementos.

“I was at the end of my rope,” Mrs. Saucier recalled. “Then, guess who shows up at the door just as I was breaking down — my friend, Kathleen.”

The impromptu visitor insisted on taking care of everything right then, giving Mrs. Saucier a much-needed rest.

Sr. Kathleen was great with college students. Through deep spirituality, a magnetic personality and reflexive hospitality, Sr. Kathleen drew together a core community of faith on the Lincoln U. campus.

Members gathered regularly for Mass and communal prayer, and for festive celebrations.

“Several of the people were musicians and they would put on these parties for all the kids we knew,” Mrs. Saucier recalled.

Jefferson City native Sister Peggy Bonnot of the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word worked with Sr. Kathleen on the Vocation Committee for the diocesan Sisters Organization.

She “was very welcoming to everyone and provided a place for the young students attending Lincoln U. to gather,” Sr. Peggy recalled. “I enjoyed working with her. She had a great desire to go to the missions.”

“The right questions”

“The grief, the heartache, it’s still right here,” said Sister Kate Reid ASC who worked closely with Sr. Kathleen in several roles.

“There are times I really miss the kindred spirit that she was, and her courage,” Sr. Kate stated.

Sr. Kathleen’s passion for justice and global solidarity permeated her work as an educator and Catholic school administrator as well as her ministry in Jefferson City.

From here, she moved back to southern Illinois to serve as the ASC province’s peace and justice coordinator.

Her Catholic upbringing in a rural locale had helped instill in her a practical piety expressed by helping people and setting them free from injustice.

She met her first ASCs when she was 6 and decided to grow up to be one of them.

She entered the ASC novitiate in Ruma in 1955 and professed final vows in 1961.

The ASC foundress, St. Maria De Mattias (1805-66), advocated boldly for people who were poor and disregarded by the rest of society.

“(Sr.) Kathleen picked that up and really led with it, and I was blessed to help,” said Sr. Kate.

Sr. Kathleen knew how to ask the right questions.

“She had a gift for analysis and discernment, and the ability to say, ‘We’ve finished analyzing this, now what are we going to do?’” said Sr. Kate.

By the mid-1980s, a growing number of religious groups in this country were harboring people who had come here fleeing violence in Guatemala and El Salvador.

Late in 1985, after months of prayer and formal discussions, an overwhelming majority of ASC sisters in the Ruma province voted in favor or harboring refugee families in their motherhouse.

“When you’re able to put the steps together and guide people to a free decision to break the law because that’s what the Gospel requires of us — that’s just such a grace,” said Sr. Kate.

Modeled on how ASC sisters in Europe helped Jewish people during World War II, Sr. Kathleen helped the sisters of her province discern what God expected of them.

“She helped us be brave and bold and be our best, be truest to our charism as Adorers,” Sr. Kate stated.

Hospitality

Sr. Kathleen hoped eventually to do relief and mission work in Central and South America.

Her friend Sister Shirley Kolmer had been serving on mission in Liberia for many years and encouraged Sr. Kathleen instead to return to Liberia with her.

Originally colonized by the United States in the 1800s as a home for people who had been set free from slavery there, Liberia weathered conflicts between the ruling class and the various indigenous groups that had been there there first.

In the 1980s, Charles Taylor organized an army of rebels to end the brutal treatment of the indigenous underclass.

That rebellion turned diabolically brutal as the nation descended into civil war and anarchy.

The ASCs and other Catholic missionaries serving in Liberia were evacuated to safety in 1990.

Late in 1991, with the cooling of hostilities and with the blessing of their congregational leaders, four ASCs decided to return to their posts as educators and healthcare workers there.

Sr. Kathleen was convinced it was time to join them.

Equipped with degrees in English, a doctorate in education and years of experience in fostering communities of faith committed to justice, Sr. Kathleen responded to requests to train teachers and to manage school finances.

She also facilitated processes that helped teachers and others explore the societal ills that became fuel for a civil war and then consider steps to remedy the causes and build an enduring peace.

Along with other sisters and a candidate for the sisterhood, she worked with parishioners organizing themselves into neighborhood faith-based communities.

She also embraced the ministry of homemaker.

She wrote to Mrs. Saucier from Liberia that she had finally found her true ministry — a ministry of hospitality.

“Hospitality was her gift — so welcoming, so affirming, so wonderful,” Mrs. Saucier stated.

She was an accomplished cook and hostess and understood the significance of food and table fellowship in the context of prayer and celebration.

“Kathleen made me very aware of the power of breaking bread — that it’s not just a sacred symbol for Mass; it’s powerful for any group gathered in prayer,” said Sr. Kate.

Women of letters

Sr. Kate kept the letters Sr. Kathleen sent her from the sisters’ convent in the Gardenville neighborhood of the capital city of Monrovia.

The letters started out humorous and optimistic. Sr. Kathleen wrote about how her camping skills came in handy when it came to cooking before the war-damaged gas and electric utilities were restored.

On Sept. 4, she wrote of receiving a visit from a mother and child. Sr. Kathleen sifted through donated clothing to find a pair of pants for the boy and a skirt and blouse for the mother.

“She was so happy,” Sr. Kathleen wrote. “She danced and laughed and hugged and kissed me. She made me so happy with her own joy but also gave me a good healthy feeling of being so ‘small-small.’”

In October, she wrote of having figured out how to bake by placing pots of smoldering charcoal inside an unused electric oven.

“It’s not top-rate but it works and I’ve baked pie crusts, cookies, cakes and brownies so far,” she noted.

She wrote about facilitating a healing workshop with the faculty of St. Patrick School in her neighborhood, focused on getting past the ugliness of the war and planning for a united future.

“Such mysteries!” she wrote. “I would never have dreamed a few short months ago how the group-process experience I’ve had would be of use to people who have endured maybe the cruelest civil war in history.”

She wrote about gathering people into small communities to help rebuild their society from the ground up.

Without such communities developing, “Liberia will not recover from the war,” she wrote.

In a February 1992 letter, she wrote of a submitting a request for funding to open a cooperative training center to help women learn marketable trades such as sewing.

She wrote of her doubts about the rebel leader’s promises to disarm and disband his militia, which was gathered just outside the city.

“The one thing that seems certain is that Taylor will not ever negotiate a peace and unification in good faith,” she wrote. “If something or someone does not stir the people to demand their country back, this debilitating nonsense may continue for years.”

At Eastertime, she wrote: “I pray that the Risen Jesus surprises you in the garden or on the road or wherever a friendly face and godly spirit will make your day!”

“Grief and fear”

On Aug. 25, 1992, Sr. Kathleen wrote of how international relief agencies tried to help 20,000 refugees moving through Monrovia to escape fighting between the rebels and a coalition of peacekeeping forces.

“Just pray that this gets resolved without an attack on Monrovia,” she requested.

On Sept. 19, she wrote that the unrest and lack of organized police protection had emboldened armed robbers to terrorize entire neighborhoods at night.

“Sunday night, Sept. 6, they got into our yard and seriously injured both guards before whistle-blowing frightened them away,” she wrote.

On Sept. 27, Sr. Kathleen wrote about how much she enjoyed baking bread.

She noted the war had moved into Monrovia in the form of armed rogues. A group of them had robbed a neighboring family twice in one night and wound up killing the father as he was defending his family.

“The grief and the fear have mingled in the neighborhood these past two weeks to create a somber and tense atmosphere,” she wrote.

She pointed out that local Church officials had condemned the fighting and terrorizing of civilians.

“But they’ve got to call upon the people to organize themselves and put a stop to this craziness,” she stated.

“Into God’s arms”

Waves of fleeing civilians clogged the roads as Taylor’s forces moved through the city late in October in 1992.

On Oct. 23, two of the ASCs living in the convent left with one of their security guards to help his sick child.

Along the way, they were shot and killed in their car.

A few days later, the other ASCs and four young girls who hoped to become sisters were waiting to hear back from them when a group of armed rebels began banging on the gate to the security wall surrounding the convent property.

They demanded money and the keys to the sisters’ car.

Sr. Kathleen, knowing what probably would happen, set out to open the gate and try to reason with them.

“I think she knew she was walking to her death,” said Sr. Kate. “I don’t know how her knees carried her except that she really, really leaned heavily into God’s arms.”

The rebels immediately shot her and the security guard who went with her.

They then entered the convent, killed the other two sisters and kidnapped the girls.

“All of them?”

Years of history with the Liberian people convinced the sisters that they might get robbed but that no one would harm them.

That’s what everyone back home believed, too.

Word reached the ASC motherhouse and the victims’ families in the early hours of Oct. 31.

A friend of Sr. Kate’s was up early, listening to the BBC World Service, and called at 5:30 a.m. to tell her the news.

“All of them?” Sr. Kate asked in shock.

“All five,” her friend reported through tears.

“By that time, I was already past blaming God for atrocities,” Sr. Kate recalled. “I would have felt that God was brokenhearted over it, too.”

She felt driven to go visit Sr. Kathleen’s mother.

“I needed to be with her mom,” said Sr. Kate. “I needed to wrap my arms around her and just be with her.”

Sr. Kathleen’s siblings and their children had gathered there. Her mother welcomed them, cried with them, relished their company and eventually told them it was okay to leave.

“I needed to be alone,” Mrs. McGuire told Sr. Kate. “Sometimes, you just have to be able to grieve in your own way.”

“At home with God”

Masses and prayer services for the sisters were held throughout the country, including in Jefferson City.

Pope St. John Paul II spoke of the sisters’ brutal death after leading the Sunday Angelus in St. Peter’s Square on Nov. 1.

“Despite the great danger” brought by the civil war, “until the end the sisters remained alongside the population threatened by the violent battles under way in that city,” Pope John Paul stated.

“May the Lord welcome into His joy the deceased religious and give consolation to their families and their sisters,” the pope prayed.

Sister Mildred Gross ASC, provincial superior of the ASC Ruma province, spoke at the end of a Memorial Mass in the Cathedral of St. Peter in Belleville, Illinois.

She referred to the slain sisters as “our first martyrs of charity.”

“Our sisters are at home with their God,” she proclaimed. “Their spirits live!”

The earthly remains of the five sisters were eventually found and sent back to the ASC motherhouse cemetery in Ruma for burial.

“Love and hope”

A sculpture depicting five sisters standing in a circle with their arms raised to heaven was created for the motherhouse property.

Sr. Kate said she wishes the sculpture would have depicted the sisters with their arms interlocked with women from all over the world.

For the 10th anniversary in 2002, she and Sr. Kathleen’s cousin gathered woven cloth from India, Liberia, Mexico, Bolivia and other countries, braided it and wrapped it over and under the arms, heads and bodies of women in the sculpture.

Sr. Kate said the five sisters’ untimely deaths left a void in the ASC community that’s still being felt.

She is particularly aware of Sr. Kathleen’s absence.

“I miss her influence, especially in crucial times of growth,” Sr. Kate stated. “She would call us and call us and actually help us build process to move beyond the status quo, to be more daring.”

Thirty years into grief and hope, Sr. Kate requested prayers “for all who struggle to survive and live with integrity and compassion as agents of a more just and loving world order.”

“May we trust that no evil is more powerful than the Spirit of God breathing in each and all who love and hope even in the midst of death-dealing forces,” she said.

This report includes information from Catholic News Service and from the book, The Cost of Compassion, by Barbara Pawlikowski.

Comments

Other items that may interest you

Services

The Catholic

Missourian

2207 W. Main St.

Jefferson City MO 65109-0914

(573) 635-9127

editor@diojeffcity.org