Helias Catholic H.S. graduate receives Texas teaching award

SCROLL THE ARROWS to see more photos.

Scott Frank flatly acknowledges that he wasn’t a stand-out scholar or athlete.

Not until he had Mike Jeffries and Chris Cooper as teachers and coaches at Helias Catholic High School.

“They taught me even more about what I was capable of than (about) the subjects they were teaching,” said Mr. Frank.

“And being that that truly changed my life, I need to pay it forward for the next generation and use my gifts and talents for humanity,” he said.

Such heat-tempered determination has helped Mr. Frank alter the trajectory of hundreds of at-risk, young lives at a public charter school near the U.S./Mexico border in Texas.

It also helped set him apart from about 600 other nominees for the 2023 James F. Veninga Outstanding Teaching of the Humanities Award, from a statewide organization called Humanities Texas.

“I considered it an honor just to be nominated, and I was blown away to be named a finalist,” Mr. Frank stated. “But there’s just no way to describe actually being chosen for the award.”

He sees the recognition as validation of his philosophy that every child can learn, with the right kind of support and motivation.

“I believe in that and put it into practice every day, even though sometimes it can be pretty difficult,” he said.

Mr. Frank teaches Advanced Placement (A.P.) and International Baccalaureate (I.B.) history and psychology at IDEA Frontier College Prep in Brownsville, Texas.

The school is a bulwark of hope in one of the most poverty-stricken locales in the United States.

Most of the students are first- or second-generation immigrants. Ninety-seven percent of them qualify for the free or reduced lunch program.

Students are admitted to the school by lottery.

Consistently, 100 percent of them graduate.

“A lot of my kids are people most of America has written off,” Mr. Frank stated. “But if you inspire kids with the prospect of college and the possibility of a better life, it gives them a really strong incentive to succeed.”

Students take a heavy load of advanced classes that can carry over for college credit.

Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, when all learning was taking place remotely, 91 percent of Mr. Frank’s A.P. psychology students passed the state exam for college credit.

“That was when those numbers were pretty much cratering all over the country,” he noted.

“Mind you, these were sophomores taking a class generally reserved for seniors,” he said.

Likewise, he hasn’t had an A.P. and I.B. history student fail the state exam in all of his 11 years at the school.

“And we cover more content and go more in-depth with them (than most other schools do),” he said.

He doesn’t water down the material.

Rather, “my kids work hard and do what I tell them, and maybe also put in some library time after school,” he stated.

Over the years, Mr. Frank has fine-tuned ways of presenting the material in a digestible manner for students of all ability levels.

“I don’t go in thinking that I’m just going to teach the good students or the ones who are going to pick it up easily,” he said. “I put it on a scaffold and try to place a handle at each level.”

Moving mountains

Mr. Frank, a son of Stephen and Jane Frank, grew up in Jefferson City, attended Immaculate Conception School and continued at Helias Catholic.

“So, I had inspiring educators all around — beginning with my parents,” he said.

His family weathered the sickness, treatment and finally the death of his brother, Michael.

Mr. Frank realized at that time that tomorrow is never a guarantee, “so why not live life to the fullest today?”

He didn’t consider himself to be a particularly gifted student until his classes with Coach Cooper and Coach Jeffries.

“It’s like a switch flipped,” he recalled.

Their lessons in perseverance and sprinting through imagined boundaries spilled over into varsity wrestling, cross-country and track.

“With Coach Jeffries, if he tells you to put a mountain on your back, you do that and run up another mountain,” said Mr. Frank. “That’s just what you do.”

Mr. Frank went on to wrestle in college and to qualify for the Boston Marathon.

“Those experiences made me who I am,” Mr. Frank stated. “I’ve seen what I’m capable of.

“Whatever people say is impossible, I love doing,” he added. “I say, ‘Let’s do it! Let’s beat the odds!’”

Toward reconciliation

Upon graduating from Helias Catholic in 2005, Mr. Frank received the Fr. Helias Award for outstanding contributions to the life of the school.

He went on to study education at Loras College, a small, Catholic, liberal-arts college in Dubuque, Iowa.

This afforded him an opportunity to study abroad in Germany, where he produced a documentary film on how people deal emotionally with the aftermath of the Holocaust.

“I talked to people in Germany, to several Holocaust survivors, to Cold War kids whose parents didn’t want to talk about the War — the shame of it — and I talked to high school kids about what it means to be German,” he said.

From there, he accepted an invitation to teach history and psychology for three years in Kosovo, a nation that had suffered massively in the civil war following the breakup of the former Yugoslavia.

“I remember President Clinton talking about Kosovo on TV when I was in seventh grade, but I had no idea where it was,” Mr. Frank recalled. “Ten years later, I was there, teaching kids who had literally survived ethnic cleansing.”

He helped organize an annual social-issues conference that brought children from the previously warring factions together to speak and listen.

He recalled how one of his students was consumed with hate for all Serbian people for the horrible atrocities some had committed during the war.

“She wound up getting paired with a visiting girl from Serbia, and they went places together and became friends, and from what I’ve heard, they’re still in touch,” said Mr. Frank.

“Right there, you could see the wheels changing direction — that nothing positive comes out of that kind of blind hatred,” he said.

“Head fake”

Originally planning to return to central Missouri to teach, Mr. Frank followed a lead to a challenging career at IDEA Frontier College Prep.

“Eleven years later, I haven’t missed a day yet,” he said.

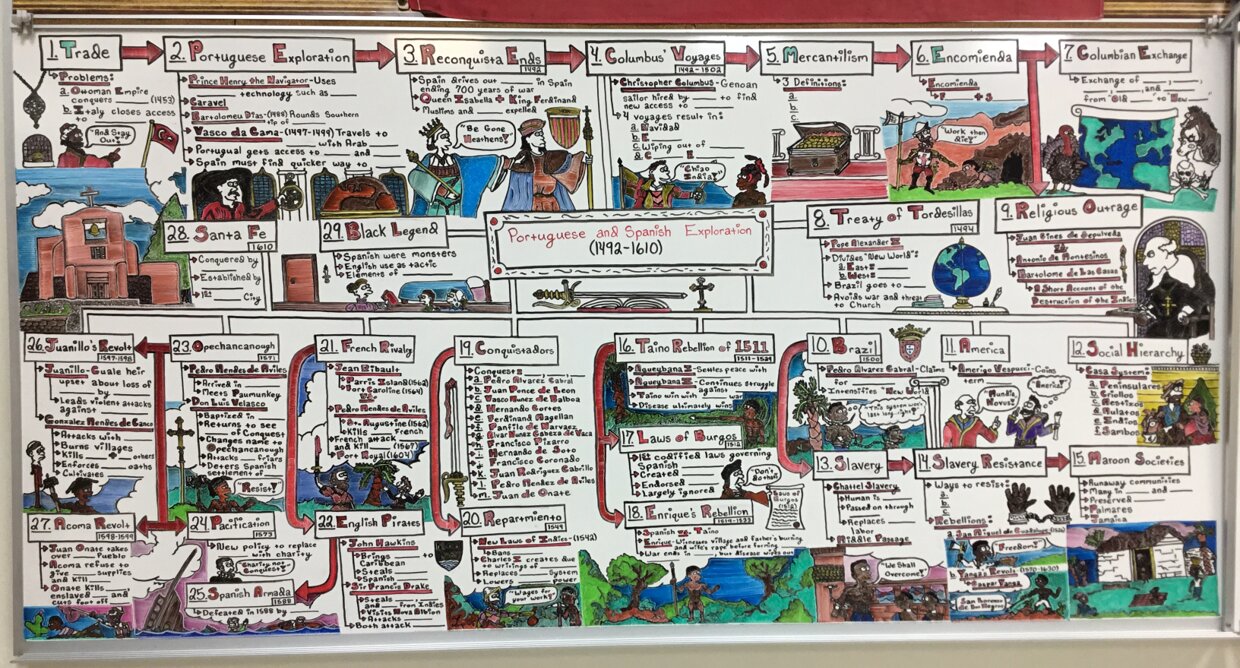

One of his techniques is to draw a large illustration of each day’s lesson on the whiteboard in his classroom.

“I use those to put a whole chapter on a map,” he said. “It’s sort of a shortcut to the notes.

“There are a lot of moving parts in history and the humanities — a lot of gears and a lot of content,” he said. “If you’re not careful, the kids just might shut down.”

Many of his students come from less-than-ideal home situations.

“My classroom can be a safe haven from all of that,” he said.

He has adorned the space with an impressive amalgamation of historical artifacts and pop-culture memorabilia.

“We have I-don’t-know-how-many bobbleheads, a fireplace, a jukebox, framed posters,” he said. “I’ve got an authentic World War I gas mask, a World War II helmet and a World War I helmet hanging up.”

There are also a couple of Captain America shields, a Luke Skywalker X-wing helmet, an old grandfather phone, a camera from the 1800s, and an antique curio cabinet containing a vintage World War II radio.

“I try to be larger than life in the classroom,” he stated. “You have to tell the story and get the kids’ attention.”

“It’s a head fake,” he said. “You think you’re learning about history, but you’re really learning about yourself and what you’re capable of, and what you can get through.

“Hopefully, this class can be an inspiration,” he said. “As if to say, ‘If you can do this, what can’t you do? You’re capable of more than you think!’”

All of this requires a delicate balance of inspiring students to want to learn, and dragging them through it when they don’t want to.

“Even when I have to pull them in the wagon, I want to at least inspire them along the way,” he said.

Aware that students can easily become overwhelmed while trying to process too much information at once, Mr. Frank encourages them to break it down into smaller pieces.

“I say, ‘We don’t have to be perfect, but we do have to be getting better,’” he said.

Most of his students are Catholic or at least nominally Catholic.

Although he can’t speak openly about his own faith unless the students ask, he’s aware of God’s presence throughout most of his work day.

“You couldn’t do this without having God as part of it,” he said. “I understand that there’s a reason I’ve been given these gifts. And if I keep them to myself, then I’m extinguishing the flame.”

“Still here”

To unwind, Mr. Frank enjoys traveling, going to the beach, running, working out and spending time with his wife, Paloma.

He said she helps keep him grounded.

“She’s the one who tells me, ‘Take it easy. It’s going to be okay,’” he said.

A biology teacher at IDEA Frontier was Mrs. Frank’s best friend and set the couple up on their first date.

They got married four and a half years ago in San Miguel de Allende in Mexico.

Late last year, Mr. Frank, like many other teachers in the post-pandemic world, was going through a very difficult time at school and seriously considering whether to give up teaching.

He was becoming convinced that despite his talent and best efforts, he wasn’t good enough to close the necessary gaps anymore.

“My parents kept telling me, ‘Work through the struggles, they are there for a purpose,’” he recalled.

He happened to receive the letter saying he had won the humanities award while enduring one of his darkest days of teaching — “and that includes when I was teaching the survivors of genocide!” he said.

He sat by the mailbox and cried for about 10 minutes.

“I had been praying, ‘God, why is it now becoming more complicated and so hard? What are you trying to teach me?’” he recalled.

“And I think this is the lesson: ‘Through all the adversity, (God is) still here.’” said Mr. Frank.

“The same guy”

The local Texas state senator came to IDEA Frontier to present the award in mid-January.

The weather was unseasonably cold, and students had permission and a legitimate reason to stay home from school that day.

Most of Mr. Frank’s students came, anyway.

“Several kids told me, ‘I knew you were getting this award, and I know you give us everything you have, so I wasn’t going to miss it,’” he said.

A week later, a student asked Mr. Frank if receiving the award had changed him.

Mr. Frank told him: “No, I’m the same guy, I’m still doing what I’m doing for the same reasons.”

Namely, inspiring his students and helping them become the best version of themselves.

“That’s what it’s about,” he said.

“Be that light”

Mr. Frank said his students and their families feel to him like part of his own family.

He often takes them to God in prayer.

“When things get hectic, I might pray to myself, ‘God, please help me do this in the right way, the way you see it,’” he said.

In times of frustration, he may stop and ask God, “What are you trying to tell me with this?”

Mindful that many educators have been thinking about leaving the profession, especially since the pandemic, Mr. Frank offered some advice to his colleagues.

“Take time to reflect about it,” he suggested. “Talk to God about it.”

He noted that although teaching can often seem overwhelming and thankless, the necessary affirmations usually come during the times of greatest difficulty.

“There’s always going to be a tunnel, but always a light, too,” he said. “If your heart and your passion are in the right place, keep doing what you’re doing.

“Keep going if you can,” he suggested. “And even if you feel that you can’t, you probably still can if you try.”

He’s inordinately grateful to all the teachers at Immaculate Conception and Helias Catholic who helped him in those early years — “who saw something in me and did something about it.”

He pointed out that if he hadn’t had teachers who saw potential in him and did whatever they could to draw it out of him, he wouldn’t be teaching today.

“You don’t know God’s trajectory for your students,” he said. “So, you need to be that light for them.”

Comments

Other items that may interest you

Services

The Catholic

Missourian

2207 W. Main St.

Jefferson City MO 65109-0914

(573) 635-9127

editor@diojeffcity.org

.jpg)