From clean water to gang violence, Salvadoran archbishop focuses on poor

Few Church leaders face having to fill the shoes of a predecessor who’s about to become an official saint of the Catholic Church.

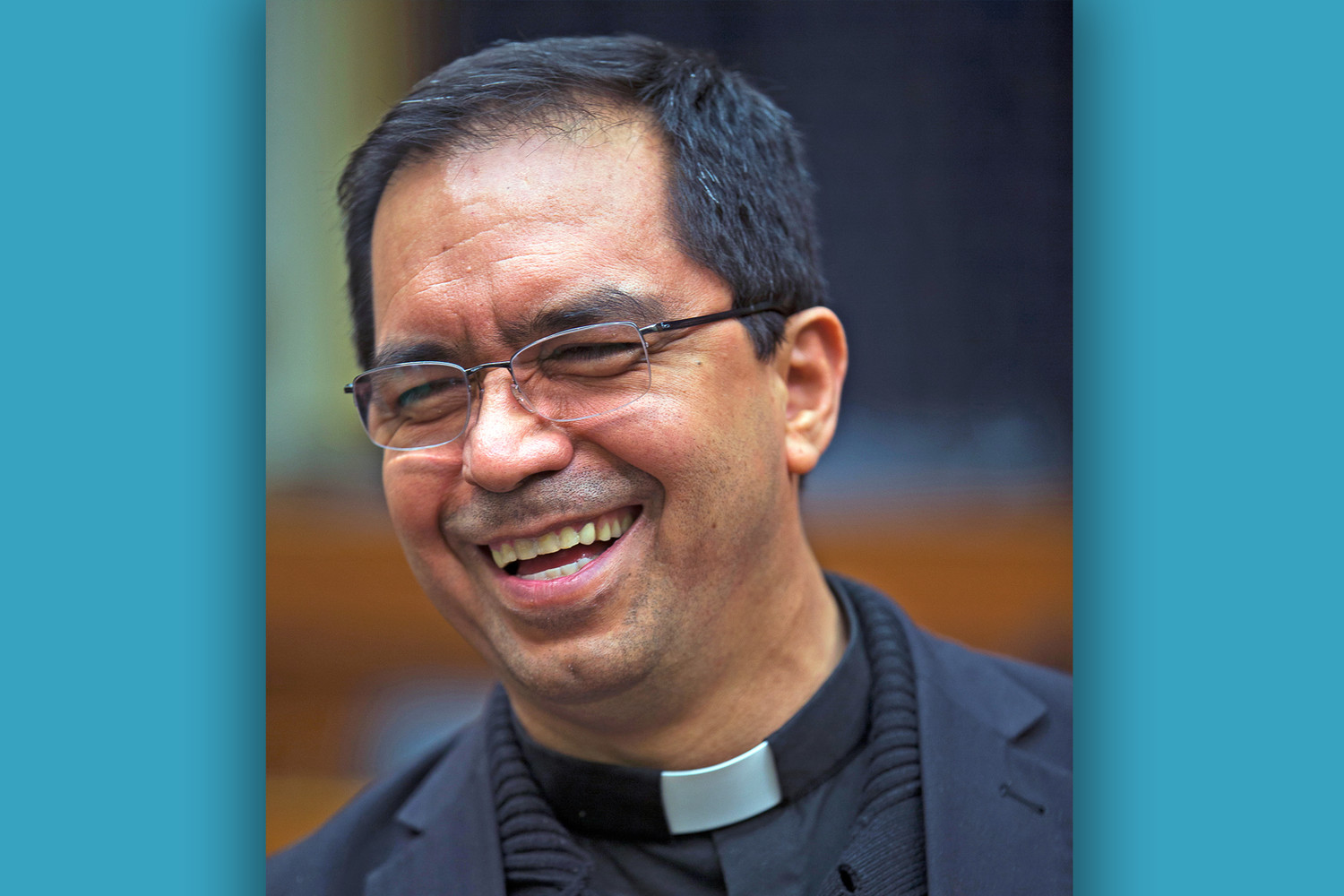

But it’s hardly on the mind of the seventh leader of Archdiocese of San Salvador, Archbishop Jose Luis Escobar Alas, whose list of worries simply doesn’t allow him time to think about it.

He carried that long list with him on a recent trip to Washington, where he was advocating for immigrants from his native El Salvador.

Along the way, the 59-year-old archbishop fielded questions about El Salvador’s mounting woes: environmental problems that include a contaminated and dwindling water supply in the country, relentless gang violence, and growing inequality and corruption that does not let his country of roughly 6 million — about half of them Catholic — find respite from its endless crises.

During interviews with Catholic News Service April 11 and 13, he discussed what troubles him the most about those problems, which he’s been dealing with since his 2009 elevation as archbishop.

“You know what’s the saddest part about it?” he asked. “They affect the same set of people the most. Yes, they affect everyone, all of us, but in principle they affect primarily the poor the most and that hurts a lot.”

Though Archbishop Escobar initially comes across as bookish and shy, his passion shines through when he speaks about the population his predecessor Blessed Oscar Romero focused on the most during his three years in the post, from 1977 until his assassination in 1980.

“As a Church, we’re with the poor,” he said. “We’re in solidarity with them and our battles are for them. That’s why we lift up our voices, for just laws for everyone but, above all, for the poor because as Blessed Oscar Romero used to say, the laws in our country are like a snake, and like a serpent, they bite the one who is barefoot.”

Last year, the archbishop spearheaded a battle backed by the Salvadoran Catholic Church that effectively led the country to become the first nation in the world to ban metal mining.

Wearing a Roman collar and gray clerical shirt, he marched along with environmentalists and activists, through the streets of the capital of San Salvador toward the country’s legislative assembly, the equivalent of Congress, to speak about mining as a process detrimental to the country’s dwindling water supply.

Just before leaving for his U.S. trip, he was checking in on his archdiocese’s efforts to collect signatures around the country’s Catholic parishes calling for a clean water act. The archbishop worries about a possible reversal of the mining law as international companies seem intent on finding a way to extract gold and other metals in the northern part of the country.

“And that just can’t happen,” he said. “Why is that? Because mining doesn’t just contaminate water but it also poisons it.”

The Washington-based Council on Hemispheric Affairs says up to 90 percent of the country’s water is contaminated by sewage and industrial chemicals. To the archbishop, it is an issue the Church must respond to because without clean water, it is the poor who become ill and ultimately die.

It is heartbreaking to visit rural and poor areas and see the faces of children suffering the consequences, he said.

“They are the protagonists of this situation,” he said. “We have many homes that don’t even have access to water. It’s a sad situation to see children sick (because of it) and how can that be? In the 21st century, how can that possibly happen?”

When Pope Francis spoke in 2017 about the universal right to access clean water, “he was thinking of countries like El Salvador,” the archbishop said.

“Water is a right, an undeniable right, (in El Salvador) and around the world,” he said. “We want to form consciences because there are still people who don’t understand the gravity of the problem.”

But if clean water is a major problem affecting the lives of so many Salvadorans, so is the relentless violence, which arrived at the doorstep of El Salvador’s clergy during Holy Week this year.

On Holy Thursday, a 36-year-old priest from the Diocese of Santiago de Maria in eastern El Salvador was shot and killed en route to celebrate Mass, hours after renewing his vows on the day the Church celebrates the institution of the Priesthood.

Authorities suspect it was a gang killing but have failed to apprehend suspects in the case.

On Easter, under a blazing sun, the archbishop marched behind the coffin carrying Father Walter Vasquez Jimenez in Lolotique, El Salvador. At his funeral Mass, he called for justice for those who took his life but also those who daily take the lives of the country’s innocent citizens.

On Capitol Hill, he said El Salvador’s problems go back centuries and have been historically caused by the idolatry of money, impunity, corruption, social injustice and inequality, and individualism. They began centuries ago, when the indigenous people of the country had to face the conquistadors who answered uprisings with massacres, stripping the native people of their lives and lands, and the best survivors could hope for were unjust salaries and inhumane treatment, he said.

The causes and effects trickled into history and toward conditions that led to El Salvador’s 12-year armed conflict, from 1980 to 1992, that left more than 70,000 civilians dead — among them two of the country’s bishops, including Blessed Romero, said Archbishop Escobar.

But it also led to the death of more than 500 Catholic laypeople as well 24 “consecrated lives,” whom the archbishop wants the Vatican to consider as martyrs.

Even after peace accords were signed in 1992, “peace never arrived,” the archbishop said at the United States Capitol April 13.

Through the years, many of the country’s Catholic bishops, including his predecessors, denounced the conditions, “but there wasn’t a response,” he said.

“Promises were made during the peace accords, but they went unfulfilled. There wasn’t justice. Impunity continued. There was an amnesty law that sought to cover up crimes against humanity,” he said.

That has made it difficult for El Salvador to move forward.

“This has led to the situation we find ourselves in today because the causes continue,” he said. “We face a collective resentment because of a lack of social justice in the peripheries, where there are no opportunities to advance.”

Though the government has made an effort to tamp down the violence, it isn’t working. With sadness in his voice, he told the story of a woman who couldn’t send her child to school past fourth grade because gangs threatened him not to go past his home’s front stoop.

A gang leader threatened the boy with death if he went into a competing gang’s territory.

The country’s young poeple watch as their parents struggle to provide for them in a country with a scarcity of employment, much less work with dignity, or even the chance to lead healthy lives, he said.

“This is the broth which the gangs cultivate,” he said.

Seemingly aware that it’s now his time to denounce injustice and call for change, he often tells others to keep working for a better day and to keep praying, because in heaven Blessed Romero and other Salvadoran martyrs intercede for them, so that one day El Salvador will be free from its woes.