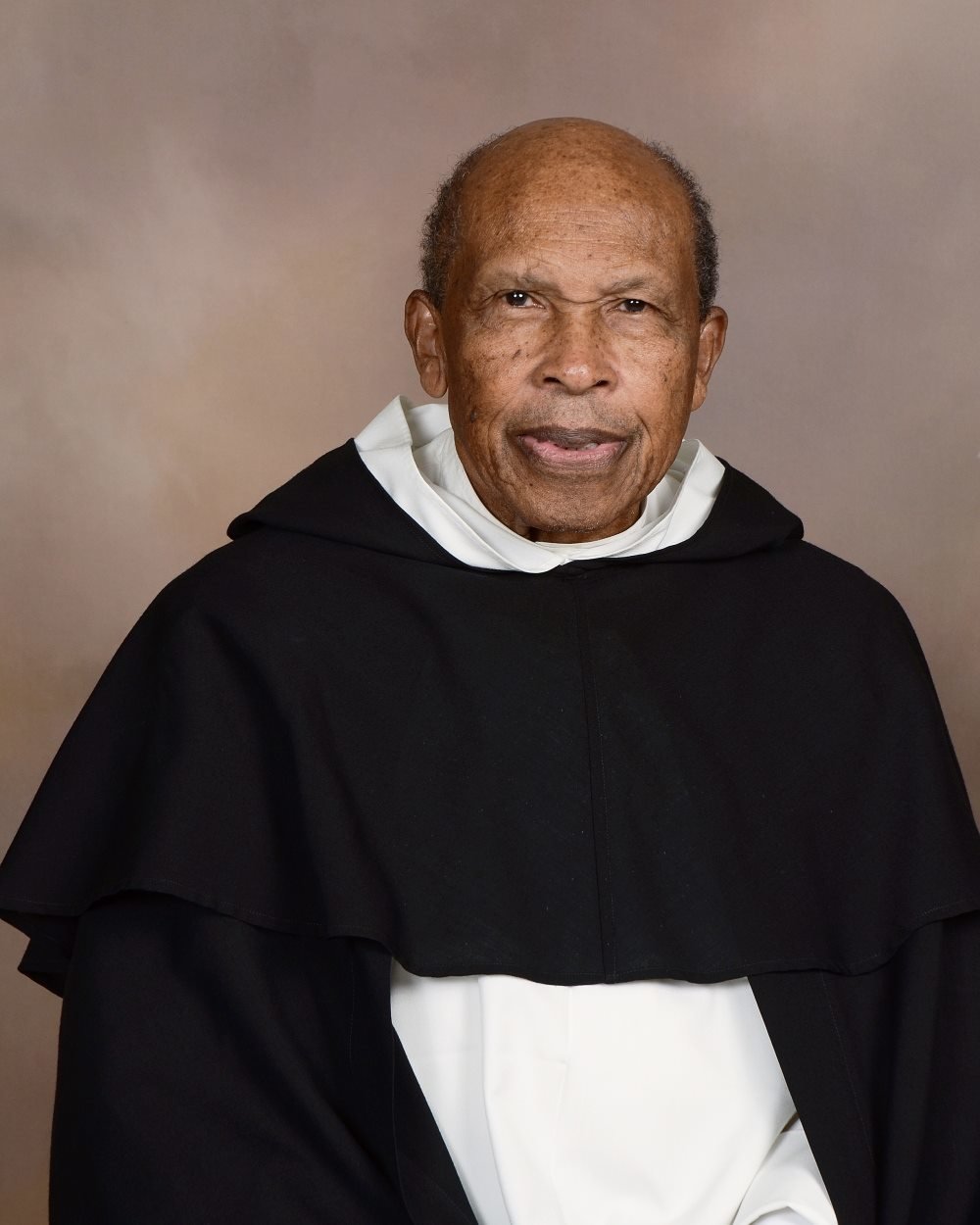

ENCORE: Father Paschal Salisbury, whose grandfather was enslaved, recalls his days as a chaplain in Jefferson City

November is Black Catholic History Month, a time to remember and celebrate the long history and proud heritage of Black Catholics.

This is an updated version of an article originally published in the March 27, 2015, edition of The Catholic Missourian:

Once while he was chaplain of the old St. Mary’s Health Center in Jefferson City, Dominican Father Donald H. Salisbury headed northeast to offer Mass in a town that shares his name.

Father (later Monsignor) Donald W. Lammers, who was pastor of St. Joseph parish in Salisbury, and his parishioners gave Fr. Salisbury a hometowner’s welcome.

“It was like I’d been away and was coming back to celebrate,” recalled Fr. Salisbury, now retired in Portland, Oregon. “They had Mass and refreshments, and a deacon gave me a copy of the abstract for the property that had belonged to my grandfather.”

That grandfather, George Salisbury, had been enslaved in Chariton County.

The Louis Salisbury family granted George his freedom on Jan. 1, 1865 — a few months before the end of the Civil War.

His emancipation document reads: “All men in the County of Chariton and the State of Missouri, I do hereby forever relieve George Salisbury from service with pay from this day, January 1st A.D. 1865.”

Fr. Salisbury has a copy of the page from a family Bible that lists the names and birthdates of many of his ancestors.

One of the priest’s cousins, now deceased, believed that George Salisbury was actually a son of Louis Salisbury.

George married the former Mary Ford of Keytesville. They eventually moved to Lawrence, Kansas.

The couple had 14 children, including a son named Louis, and Fr. Salisbury’s father, Adam.

Two generations from slavery

Fr. Salisbury, who is African American, was born on June 6, 1928, in Lawrence.

He grew up in an era of segregation and limited opportunities for Blacks.

He was not raised Catholic but enjoyed listening to Bishop Fulton Sheen’s uplifting Catholic radio programs.

“I sent away for a rosary and when I got it, I didn’t know how to pray it,” he recalled.

He spent two years in the U.S. Army, which was segregated at that time.

Six months after the future priest’s tour of duty ended, President Harry S. Truman integrated the U.S. Armed Forces.

“I saw that as an opportunity, so I signed up for the Air Force,” Fr. Salisbury recalled.

A gifted musician who had studied piano and organ, he accompanied services in the Protestant chapel on the base where he was stationed.

He wished he could practice late at night, but the chapel closed early.

“I told that to a Catholic friend, and he said I could practice the organ in the Catholic chapel,” which stayed open later, Fr. Salisbury recalled.

He wound up befriending the priest and several Catholic congregants on the base. Before long, he decided to receive instructions and become Catholic.

He was initiated into the Church at age 21 in 1948.

After reentering civilian life, he began thinking about the Priesthood.

He contacted representatives of several Catholic orders and was advised each time to become a brother or not to pursue religious life at all.

But he believed God was calling him to be a priest.

He moved to San Francisco and joined St. Dominic parish, which was staffed by the Order of Preachers (Dominican Order).

While studying business at the University of San Francisco, he sang in the parish choir and became active in the Holy Name Society.

After graduating second in his class at the university, he asked the Dominicans to help him answer his priestly calling.

“They knew me, and one of the brothers said he’d vouch for me,” Fr. Salisbury recalled.

In August 1961, he entered formation for the Dominicans in Oakland, California.

He was given the religious name Paschal.

On June 16, 1967, in the Cathedral of St. Francis de Sales in Oakland, Bishop Floyd L. Begin, now deceased, of Oakland ordained him to the Holy Priesthood.

He was the Dominicans’ first African American priest in the United States.

“No, thank you. I’m Catholic”

Hoping to serve as a chaplain, Fr. Salisbury undertook a year’s training in pastoral ministry at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., followed by additional training at hospitals in California and New York.

His provincial appointed him associate director of the All Saints Catholic Student Center at Arizona State University in Tempe.

In 1979, he sought permission to look for a ministry closer to his sister in eastern Kansas, who had developed health problems.

That’s what brought him to Jefferson City.

Here, he found a welcome reprieve from most of the implicit and explicit prejudice he had encountered during much of his discernment and early years of Priesthood.

He was the first African American priest in the Jefferson City diocese since its founding in 1956.

At St. Mary’s, he dove earnestly into his ministry.

Dressed in his white Dominican habit, he knocked on a patient’s door and offered her Holy Communion.

She said, “No, thank you. I’m Catholic.”

“I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry,” Fr. Salisbury later told a fellow priest.

But people did get to know their chaplain as he continued doing what God called him to do: comfort the suffering, hear confessions, distribute Holy Communion, anoint the sick, console the bereaved, offer Mass and serve as a living reminder of God’s love and friendship.

Life in the Capital City

While assigned to St. Mary’s, Fr. Salisbury lived in the Immaculate Conception Parish Rectory, taking his meals with the other priests and offering one of the Sunday Masses there each week.

Fr. Salisbury thrived on the camaraderie with his fellow priests. He enjoyed visiting neighboring parishes each Advent and Lent to help out with communal reconciliation services.

He also enjoyed ministering to the Carmelite Sisters of the Divine Heart of Jesus who were living and serving at what was then known as St. Joseph Home for the Aged in Jefferson City.

His pastors were Father Richard Cronin, now deceased, and then Father (later Monsignor) Michael T. Flanagan.

“He’s a lot of fun, a really neat guy, very gentle and unassuming,” Msgr. Flanagan said of Fr. Salisbury. “People were very good to him. The people at I.C. really loved him.”

A handful of associate pastors also served at I.C. during Fr. Salisbury’s time there, including Father Ignazio C. Medina.

“He’s very witty and insightful, and very talented,” Fr. Medina noted.

As much as parishioners enjoyed having him around, Fr. Salisbury’s spiritual gifts found their purest expression at the hospital.

“The people there loved him because of his gentleness, his unobtrusiveness,” said Msgr. Flanagan. “He was very kind with his patients and very, very gentle. He had this great laugh that he’d bring with him wherever he’d go.”

Monsignor Gerold J. Kaiser, now deceased, was vicar general while Fr. Salisbury was in the diocese.

“He was a good supporter of mine,” Fr. Salisbury recalled. “He said I could have probably been a bishop because people liked me.”

The Dominican priest still uses the chalice Msgr. Kaiser gave him.

Two more decades

In 1984, Fr. Salisbury started the next phase of his hospital ministry, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

After a few years, his provincial summoned him to work in the office at the Shrine of St. Jude Thaddeus in San Francisco.

From there, he went to Holy Cross Hospital in Fresno, California, to be a chaplain.

He later served in San Francisco, then in Los Angeles.

In 1992, he became a Catholic chaplain at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ Southern Oregon Rehabilitation Center and Clinics (SORCC) in White City.

He remained there until his retirement in 2005.

Since then, he has resided in Dominican communities in San Francisco and Portland, Oregon.

Hoping to stay in touch

Now in his 90s, Fr. Salisbury offers daily Mass, hears confessions and prays the Liturgy of the Hours several times a day with the other Dominicans at Holy Rosary Priory in Portland.

He reads The Catholic Missourian and remains in touch with several people he got to know in Missouri.

Several people from Jefferson City have visited him during their travels, and he once got to return the favor about a dozen years ago.

He was on his way for another visit to Jefferson City in 2014 when he fell in Kansas City and damaged his rotator cuff.

The aftermath was almost unbearable.

“The pain was unbelievable,” he said in 2015. “I thought had a blood clot.”

But he treasures the memories of friends still living and those who have gone to God in the state where his grandfather waited for and finally got his first taste of freedom.

Some of the information in this article came from an article by the late Estelle Lammers in the Nov. 30, 1979, issue of The Catholic Missourian.

Comments

Other items that may interest you

Services

The Catholic

Missourian

2207 W. Main St.

Jefferson City MO 65109-0914

(573) 635-9127

editor@diojeffcity.org